For more than a decade, public opinion polls reinforced the notion that Americans did not support marriage equality for same-sex couples. More than 10 years after pollsters began tracking the question in the mid-1990s, results would have you believe a majority of Americans did not support marriage equality until, quite suddenly, they did.

For more than a decade, public opinion polls reinforced the notion that Americans did not support marriage equality for same-sex couples. More than 10 years after pollsters began tracking the question in the mid-1990s, results would have you believe a majority of Americans did not support marriage equality until, quite suddenly, they did.

In 1996, Gallup found that only 27% of American adults believed marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized as legal, with the same rights as traditional marriages. That percentage rose to 35% in 1999 and hovered around 40% until 2011 when, suddenly, a majority of Americans (53%) were supportive. Pew uncovered a similar trend. The moment of critical mass for marriage equality occurred in the early 2010s, begging the question: Why the sudden change? Was there a dramatic shift in public sentiment?

The sudden surge in support of gay marriage coincided with political changes to the way same-sex marriages were handled by law enforcement. In particular, President Barack Obama instructed the Department of Justice to stop defending a federal statute prohibiting same-sex marriage in 2011. Two years later in 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled California’s Prop 8 unconstitutional before finally ruling on the constitutionality of same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

Coined by Dale Miller and Cathy McFarland in 1991, pluralistic ignorance is a social phenomenon where people erroneously believe their privately held beliefs are different from those around them. Despite best practices in survey methodology at the time, public opinion pollsters were unable to accurately measure Americans’ support for same-sex marriage in the years preceding Obergefell v. Hodges.

The problem: Distorting filters

When, why, and under what circumstances does public opinion fail? Below are a few of the distortions at play when traditional public opinion polling fails.

Conformity Bias

Humans are social creatures and, as such, we are influenced by the opinions of other people. A need for relatedness is an evolutionary adaptation that has propelled humans to the top of the proverbial food chain; we have evolved to be able to make use of private knowledge and social knowledge to make more informed decisions that keep us alive individually and cohesive on a collective level. Yet the very adaptation that conferred such a monumental advantage can work to our disadvantage.

One filter through which individuals’ private opinions are distorted in the aggregate is people’s predisposition to conform to their (mis)perception of the majority. Conformity bias is the tendency to express an opinion in accordance with the majority or one’s perceived in-group, even if one doesn’t truly hold that opinion. The problem is that for a myriad of reasons (e.g., looking-glass self, third-person effect, hostile media effect) people are not very good at estimating what the majority opinion is on a given topic. Decades of psychological research on social influence demonstrate the robustness of the effect conformity bias has on the general population’s publicly professed opinions.

In what has become a seminal experiment in social psychology, Solomon Asche (1951) demonstrated the power of conformity bias. In his experiment, research subjects were posed with a series of tasks: observe a set of illustrated lines of varying lengths and then identify which one matches a target line. Though it may sound complicated, the task was actually quite easy and the answer unambiguous. The experimental trick is that research subjects provided their answer after a group of confederates also completed the task. For planned tasks where the group of confederates provided obviously wrong answers, participants were significantly more likely to conform with the factually incorrect majority.

Conformity bias extends beyond highly controlled laboratory settings. For example, in a series of studies on drinking behaviors among college students, Deborah Prentice and Dale Miller found that college students overestimated the extent to which their peers were comfortable engaging in frequent and dangerous bouts of binge drinking. Even though individuals, on average, privately believed they were much less comfortable with dangerous drinking practices than the average student, they continued drinking dangerously to satisfy the perceived social norm.

In both scientific examples, perceived minority status led individuals to adopt a conformity bias, leading to self-silencing and an illusory majority. This is deeply problematic when measures of public opinion that are used to inform candidate positions, government policies, or even to help individuals benchmark their perceptions against that of the general public, are inherently biased.

Complex Tradeoffs

Whereas individuals may feel an incentive to intentionally modify their private belief in accordance with perceived public opinion, there are times when public opinion polling makes it difficult for individuals to directly report their beliefs, attitudes, or preferences. Even if an individual can accurately express their opinion, no issues exist in a vacuum, and an accurate appraisal of one’s own opinion should acknowledge that. Do you support funding Social Security and Medicare? What about education? Defense? The truth is that we live in a society operating on limited, albeit vast, resources, and we must make difficult decisions about how to prioritize and allocate those resources.

Public opinion research has historically tended to ask individuals about their policy preferences without acknowledging the reality that issues are not independent of others. Do you support or oppose affordable healthcare for all Americans? The question ignores that support and investment for such a policy comes at the cost of other potentially urgent policies. Public opinion research that doesn’t acknowledge difficult tradeoffs in urgency and resources fails to capture the public’s true social policy priorities.

In situations where there is limited time or resources, understanding public opinion requires understanding the tradeoffs people are willing to make to get what they want.

Leaky Abstractions

Humans are bombarded with a deluge of information every day and are forced to make decisions based on that information. But no single person has the time nor proclivity to parse apart the signal from the noise, process all relevant data, and make an informed decision for every situation they are confronted with. As such, human brains have evolved to employ mental shortcuts or heuristics. Using past information and abstract reasoning, individuals use a limited sample of data and previous experience to make informed, if not perfect, judgments.

Leaky abstractions are simplified, high-level heuristics lacking details that we use to characterize their worldviews. So-called leaky abstractions severely distort individuals’ private beliefs and preferences by stripping complex questions or issues of the significant details that determine private preference. The seductive convenience of leaky abstractions leads to intractability and intransigence. In other words, a leaky abstraction occurs when multiple individuals have materially different interpretations of the same core concept because of how each individual privately frames the issue.

Consider, for example, what it means to be “pro-immigration.” Individuals who view immigrants favorably will find commonality in their abstract value, but “pro-immigration” is not a meaningful preference when it comes to policy. There are probably a dozen or more concrete policy options related to immigration and two people who both profess to hold the same abstract value could have significantly different opinions about the concrete policy decisions such that, in the details, their stances on immigration look nothing alike. Two pro-immigration Americans may hold completely opposing views about the need for high- and low-skilled labor, the legal status of the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the country, border security, and interior enforcement.

Oftentimes, leaky abstractions boil down to the lowest common denominator: adversarial identity politics. They allow individuals to hastily adopt a vetted, yet imprecise, opinion on a complex topic.

Private opinion research: Defined

In contrast to public opinion polling, Gradient has begun adapting survey methods that circumvent distorting filters and measure Americans’ private opinions. At the end of the day, private opinion methods attempt to give voice to Americans when it may be hard to truly speak their mind.

Private opinion methods are survey methods designed specifically to elicit people’s true opinions in the presence of distorting filters, like strong social conformity pressures, complex tradeoffs, and leaky abstractions.

Gradient is committed to advancing this field by leveraging new methodologies in the context of private opinion research that get beyond traditional limitations of public opinion and help create an understanding of the public that is capable of informing efforts to build people-oriented systems and establish a culture of social trust.

Public opinion vs. private opinion methods

Below are some methodological distinctions to further elaborate the difference between public and private opinion methods.

|

Public opinion methods |

Private opinion methods |

|

|

Survey question type |

Direct questions |

Indirect questions or forced tradeoffs |

|

Analysis type |

Simple frequency and count data |

Complex statistical modeling |

|

Social distortions |

Vulnerable to distorting filters |

Protected from distorting filters |

|

Sample size required |

Requires smaller sample sizes |

Requires larger sample sizes |

When should you use private opinion methods?

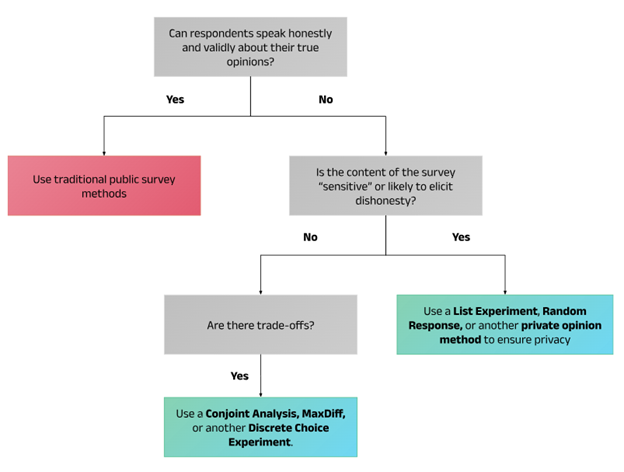

Even though private opinion methods offer solutions to impediments like preference falsification and conformity bias, they aren’t always the advisable method. Oftentimes, when there isn’t any threat of distorting filters, a simple public opinion poll is the best tool for the job.

Furthermore, even when private methods are deemed worthy, which one should a savvy survey methodologist select? Private opinion methods are not “one-size-fits-all.” To support the curious and discerning researchers, we put together a basic flowchart to facilitate decision-making.

If your organization needs to elicit the true, private opinions of the public or consumers, Gradient is here to help. We'll use the most advanced methodological solutions, such as a list experiment, conjoint analysis, or MaxDiff experiment to uncover your audience's hidden truths. Let us know your research needs!